One of concrete’s most defining properties is its change from a fluid state into a rigid one during the process of curing. The liquid concrete is poured in a mould that can hold almost any shape, thus presenting the other main characteristic of concrete: it can take almost any form and texture. Traditionally these two properties are interdependent and over past times refined, developed and taken advantage of for architectural expression as well as for industrial efficiency.

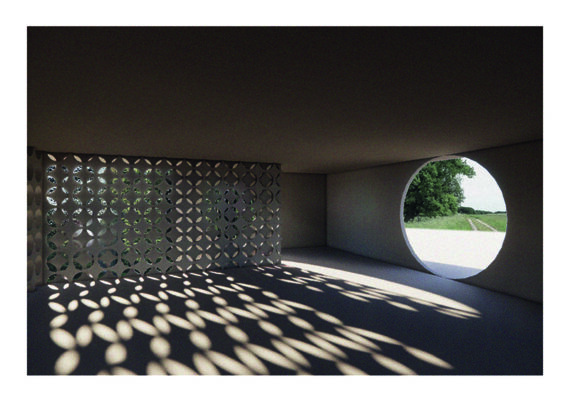

We all know ‘beton-brut’ or ‘brutalism’ as one of the more expressive styles of applying concrete. Making most of its capability to mirror the formwork textures and combining form with concrete’s mass as a major feature to create architectural or sculptural works expressing sturdiness, robustness, or durability. Similarly, the formwork textures and shapes can be utilized to express elegance and sophistication, through a refined play with shadows and smoothness, slender structures and curved surfaces. Due to being able to produce almost any form, concrete elements can directly show structural principles or shape complex spaces.

Current developments on formwork technologies aim to industrialize the processes of creating formwork. From a more craftmanship-like technique towards a more robotically driven one. In part these developments are driven by the ambition to extend parametric design possibilities to economically viable manufacturing processes, thus creating the opportunity for designers and clients to create complex and efficient structures, while maintaining an abundance of formal options to explore. Parallel ambitions on topics as sustainability and circularity also demand adaptable systems that minimize waste materials and optimize speed and accuracy. The developments range from CnC-milling formwork parts to 3D-printing directly with concrete, eliminating the formwork altogether. In between we'll find experiments with fabric formwork systems, 3D printed formwork with reusable materials, robotically assembled traditional formwork materials, and so on.

What remains are the properties of concrete that define its architectural and structural use, its textures and the shapes it can take and create. FORM-WORKS intends to identify specific concrete potential in terms of production as well as in terms of expression and presence.

The 9th Concrete Design Competition on FORM-WORKS asks students of architecture, design, and engineering to explore and exploit the potential of concrete’s properties with respect to any notion of FORM-WORKS. These can be related to inherent material properties, concrete’s production processes, and its application in new or existing structures. They may address aesthetic desires, structural systems or fabrication methods and comment on economic realities, sustainability demands or social issues.

This competition does not prescribe a specific location or program; participants can choose a context of their own that supports their fascinations and ambitions and that fits an acute presentation of their ideas. Proposals may range from objects, furniture, and architectural details, to housing, landscape interventions, complex buildings, infrastructure, and structural systems. Competition entries need to address technical and functional aspects as well as formal and programmatic ones – ideas need to be tested through design proposals to convincingly demonstrate their potential. They will be reviewed on the combination of inventiveness in addressing the competition’s theme and architectural implications.

The 9th Concrete Design Competition – FORM-WORKS runs in four European countries during the academic year 2019 - 2020. National laureates will be invited to participate in a weeklong international workshop in Ireland (August 23 - 29, 2020) facilitated by the industry featuring renowned lecturers, experts, and critics, further exploring concrete and FORM-WORKS.

9TH CONCRETE DESIGN COMPETITION ON FORM-WORKS

FORM; 1 the visible shape or configuration of something; style, design, and arrangement in an artistic work as distinct from its content 2 a particular way in which a thing exists or appears 3a type or variety of something 4 the customary or correct method or procedure 11 another term for shuttering

ORIGIN based on Latin forma‘a mould or form’

WORK; 1 activity involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a result 3 a thing or things done or made; the result of an action 4 (works) a place or premises in which industrial or manufacturing processes are carried out 8 (the works) everything needed, desired, or expected

-work> combining form denoting things or parts made of a specified material or with specified tools: silverwork

OXFORD DICTIONARY OF ENGLISH

COMPETITION RESULTS

AB270 - Dutch Light, Dutch Landscape

Netherlands (Nominee)

Alexander Beeloo – Amsterdam Academy of Architecture

AC120 - Defensive Architecture as Landscape

Ireland (Highly Commended)

John Theodore Moran – Queens University Belfast

CA214 - MODULAR e-Bench

Netherlands (Nominee)

Nigel Flanagan, Bethany Kiss, Sofia Pavlova & Leon Thormann – Delft University of Technology

DD462 - Velvet Concrete

Netherlands (Second Prize)

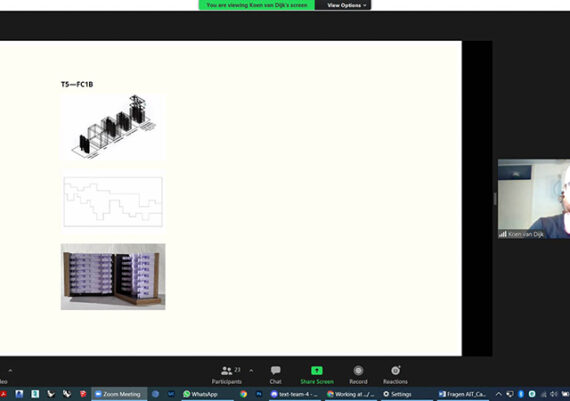

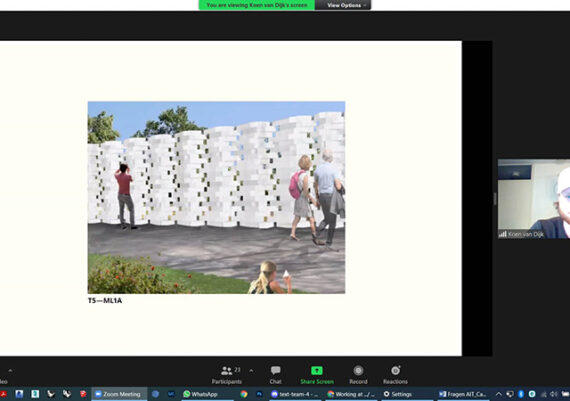

Michiel Derikx & Koen van Dijk – Eindhoven University of Technology

EM996 - discrete

Belgium (Honourable Mention)

Eva Baplu, Manon De Backer & Thomas De Jonckheer – Thomas More Mechelen

ES020 - ECHOSEAT

Netherlands (Nominee)

Nick van Dijke, Marijn van Rozendaal, jahan Tahamtan & Luuk Verhagen – Fontys School of Fine and Performing Arts, Tilburg

GC735 - CO2 Capture Concrete Facade Panel

Ireland (Highly Commended)

Kate Newe – University College Dublin

HB797 - UHPC Pavillon

Germany (First Prize)

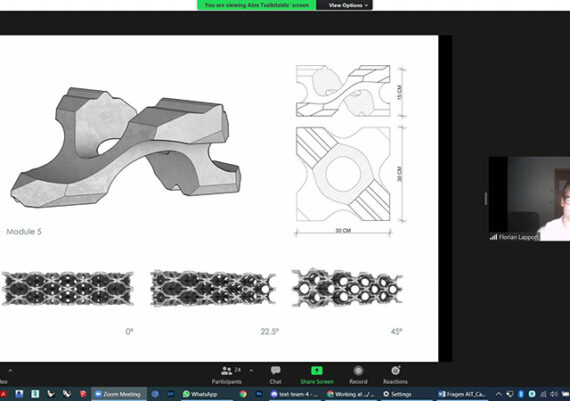

Andras Kispal, Florian Lapport & Yasin Roßbach – TU Kaiserslautern

II111 - Intelligente Ruine

Germany (Honourable Mention)

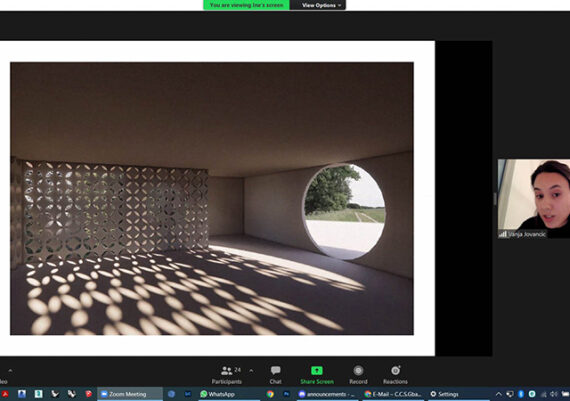

Ayoub Azzabi, Vanja Jovancic & Goran Travar – TU München

KR999 - CHAINLINK

Netherlands (Honourable Mention)

Kyra Heijblom & Rick Wassenaar – Eindhoven Univeristy of Technology

MS999 - Multi-Facade

Netherlands (Third Prize)

Clara Beckers, Jemina Lai & Hannah Zhu – Delft University of Technology

SC417 - Slag-Crete

Netherlands (Nominee )

Jiri Brakenhoff, Julianne Guevara & Diego Toribio – Delft University of Technology

SW580 - Acute Acoustics

Netherlands (First Prize)

David Fritz, Siri Mulleners & Saskia Tideman – Delft University of Technology

VO910 - CONCURVE

Belgium (First Prize)

Wouter Persyn, Ine Verhaege & Dries Voet – Thomas More Mechelen

JURY REPORTS

NATIONAL JURIES

Belgium

Guy Mouton (Jury Chair), Olivier Gallez, Hilde Huyghe, Tania Vandenbussche & Adrien Verschuere

Germany

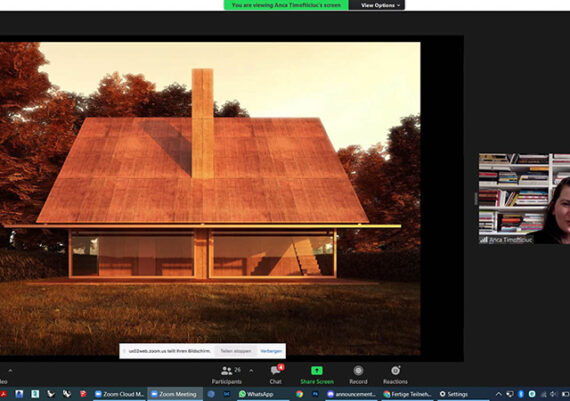

Sandra Hofmeister, Markus Holzbach, Jan Kampshoff, Ulrich Nolting, Holger Techen & Anca Timofticiuc

Ireland

Donal O'Donohue, Jeana Gearty, Steve Larkin & Jim Mulholland

Netherlands

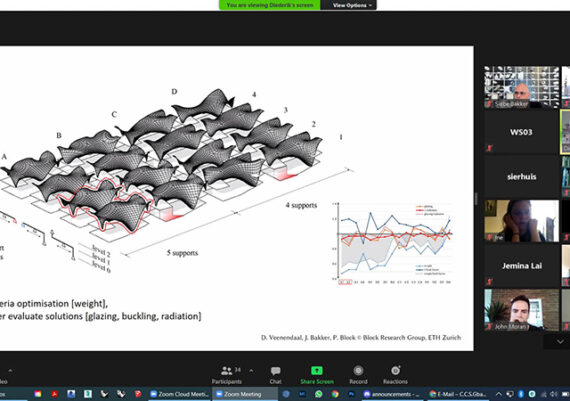

Juliette Bekkering (Jury Chair), Diederik Veenendaal, Marieke Kums, Max Rink & Niels van der Hulst

FORM-WORKS: a virtual master class on digital design and digital fabrication of concrete

The 9th Concrete Design Competition for European students of architecture, engineering and design was hit by COVID-19 just like so many other activities and events over the last year and a half. While originally planned to culminate in Dublin in August 2020 with our characteristic award for national laureates - a weeklong, hands-on international master class working with and exploring the properties of concrete – we had to postpone. Unfortunately, by August 2021 the international situation still had not improved enough to allow us to host an in-person event for 25+ people from all over Europe. We therefore looked at other ways to deliver the international concrete master class. We embraced the idea of a fully digital (distant) practice in which both design processes and fabrication methods would be tested and explored - all within the original timespan of five consecutive days.

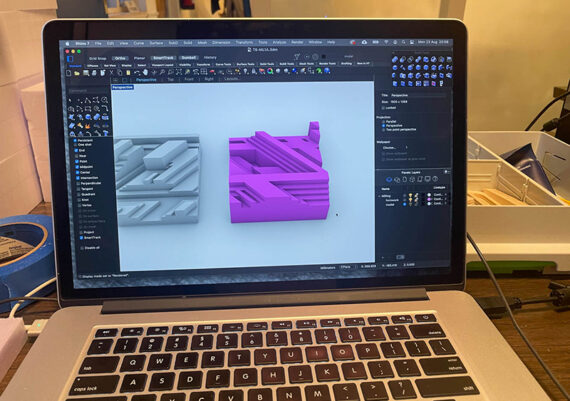

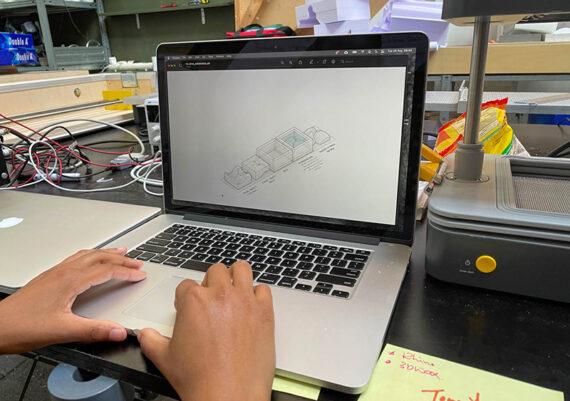

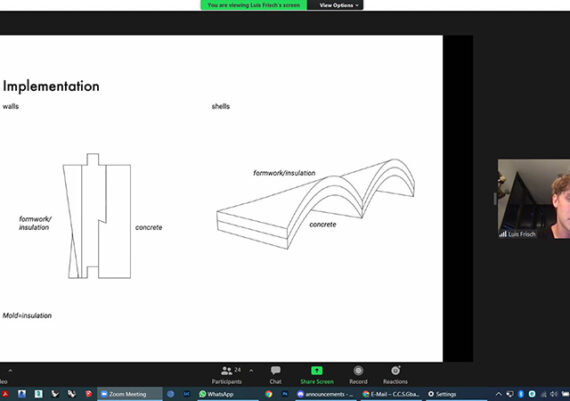

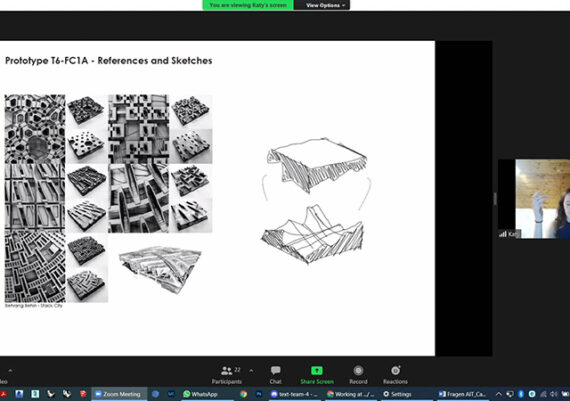

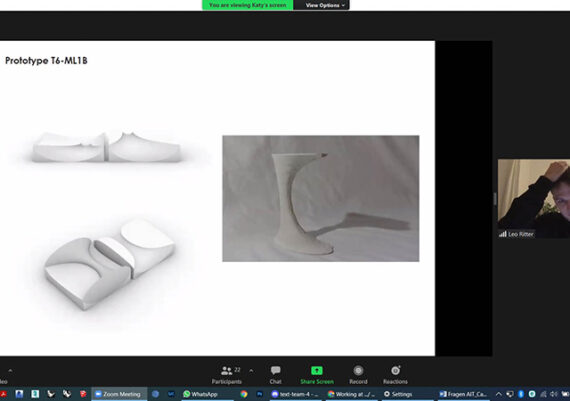

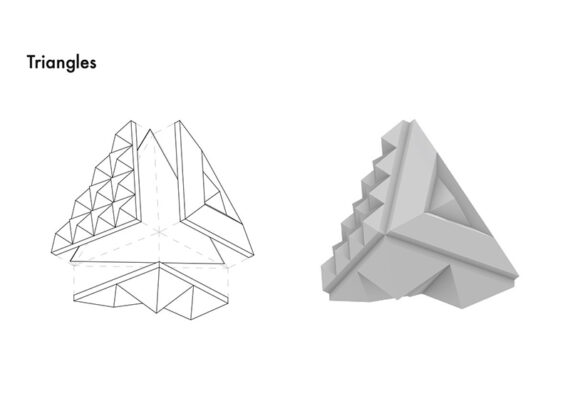

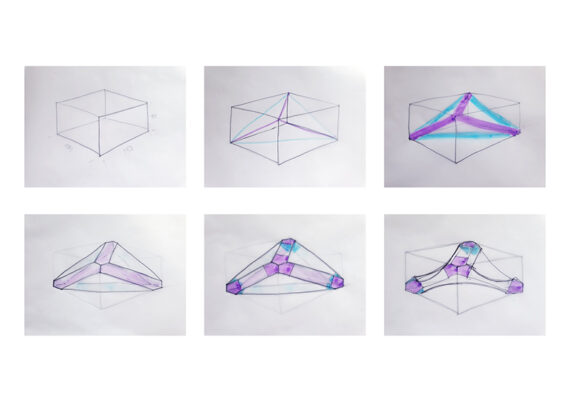

The competition theme of FORM-WORKS presented an excellent framework to research relations between digital design processes ranging from experimenting with online design and critic sessions to various digital fabrication techniques to develop the formwork for concrete objects.

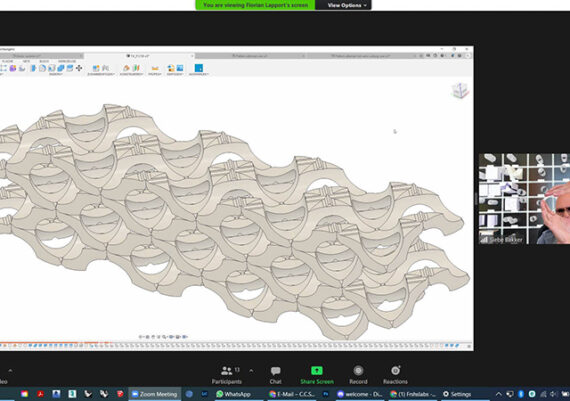

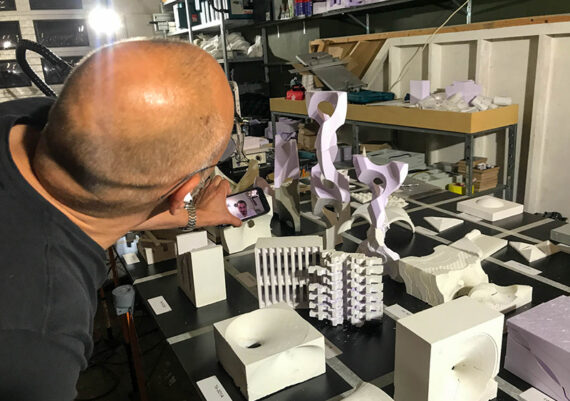

The online design sessions, tutoring, critics, and lectures worked efficiently, not least due to the well-trained participants who had experienced similar circumstances for over a year in their respective universities. Being literate in many different online discussion, presentation, and collaboration platforms, from WhatsApp, Zoom, Discord as well as Miro and Google Drive, we were able to cater to all specific needs.

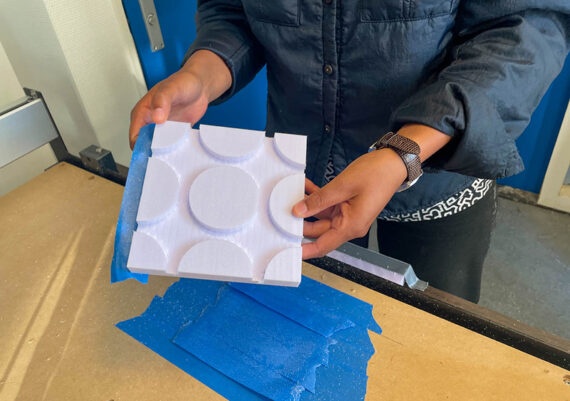

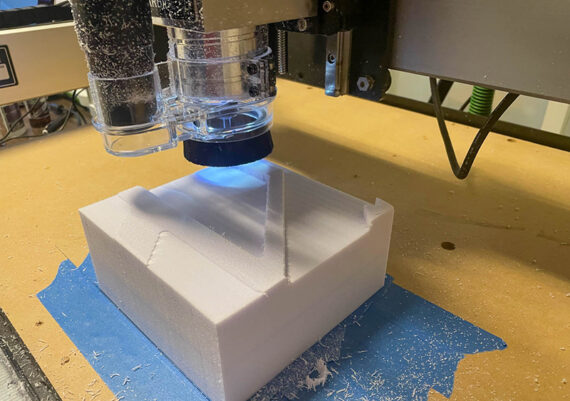

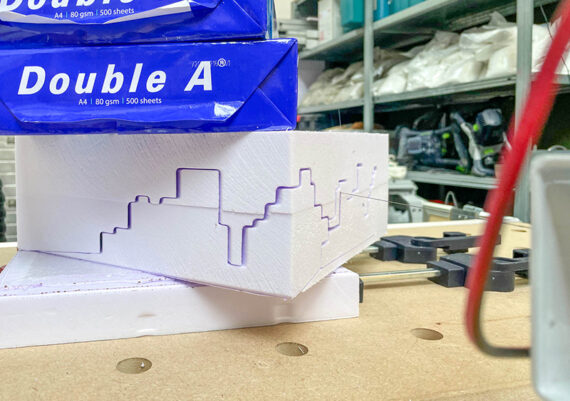

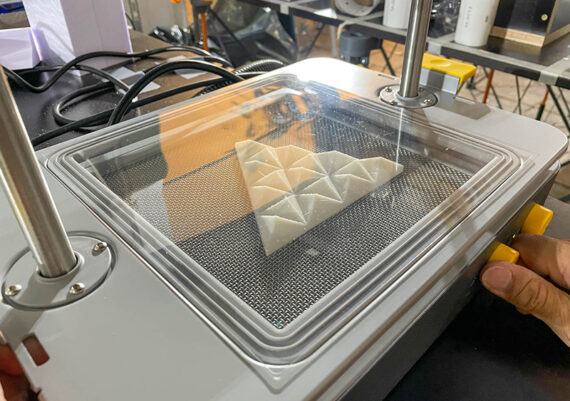

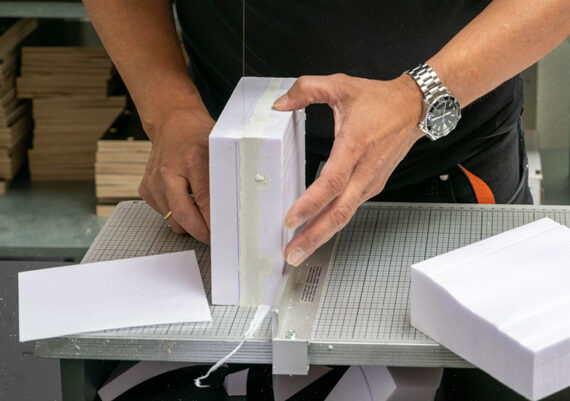

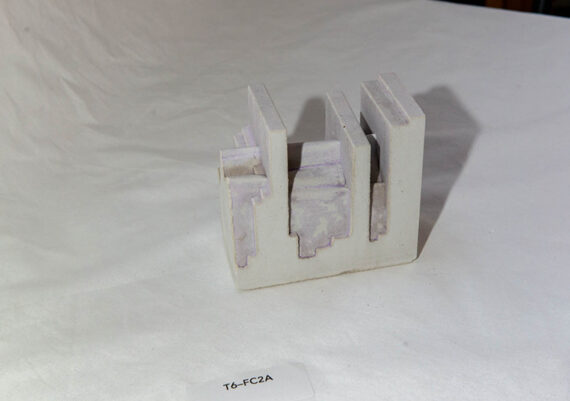

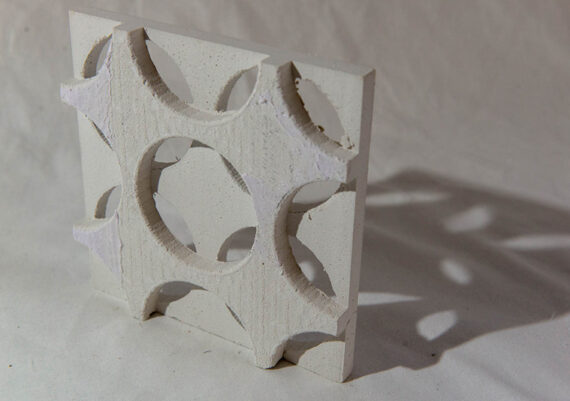

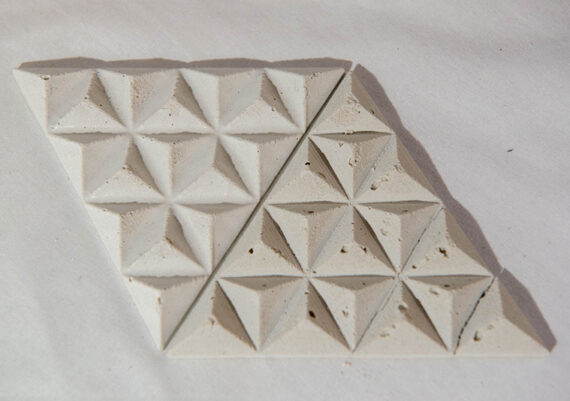

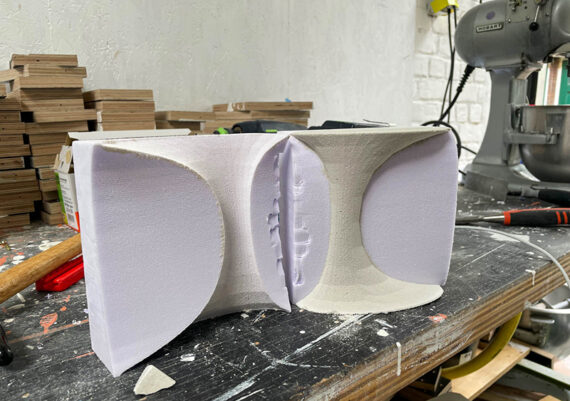

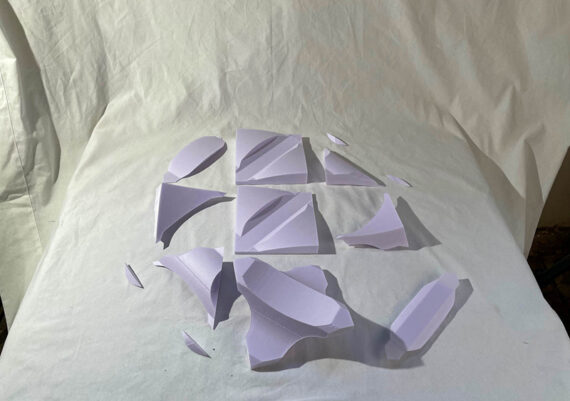

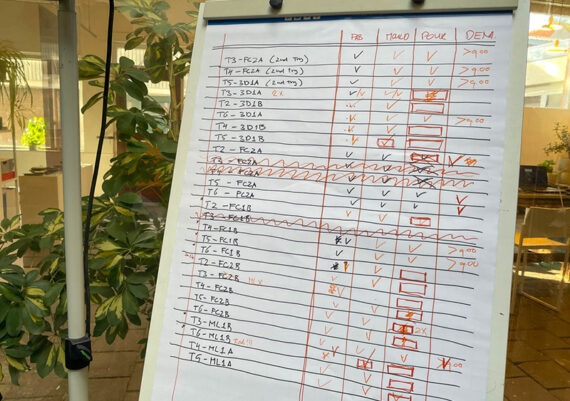

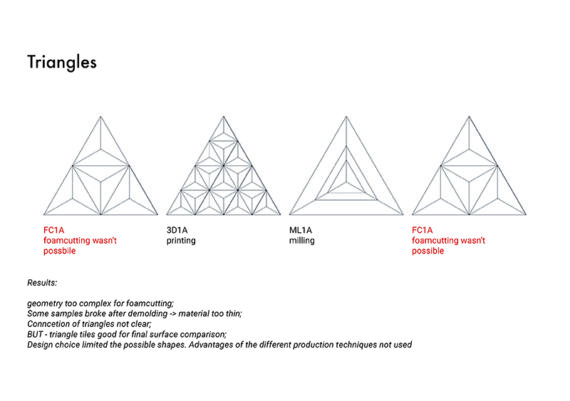

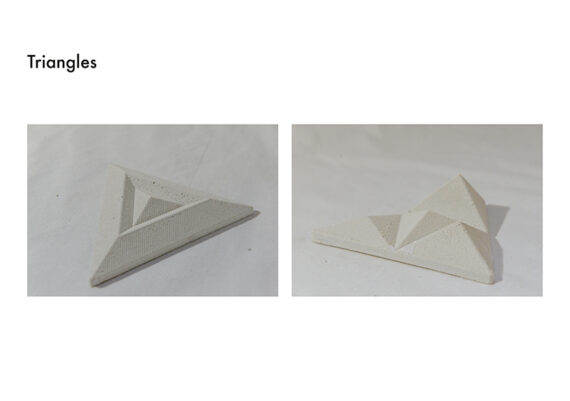

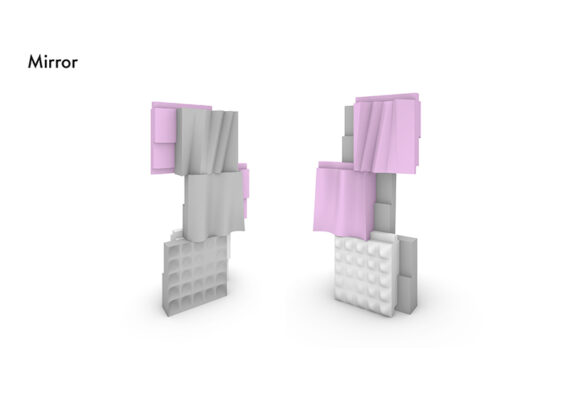

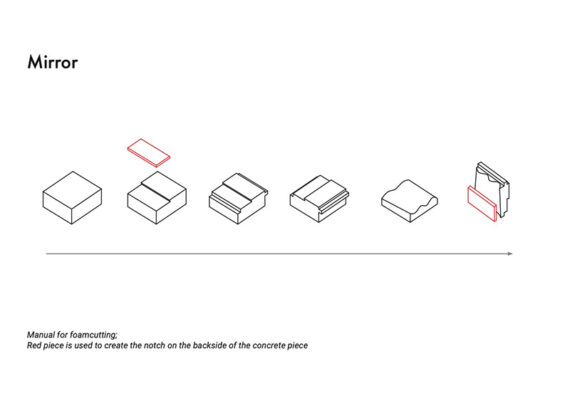

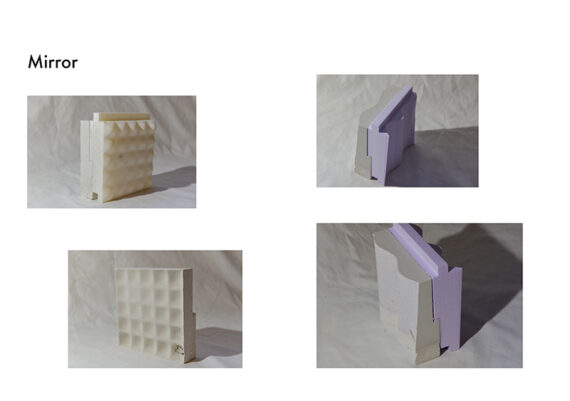

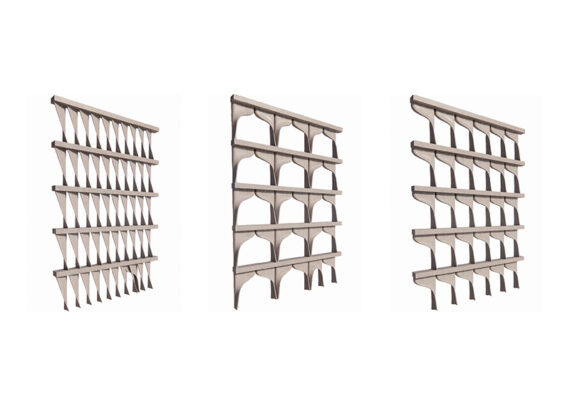

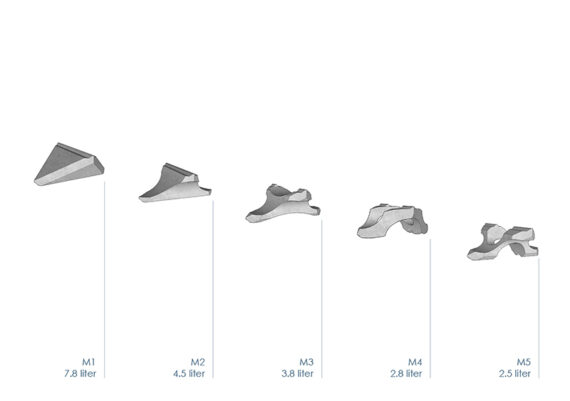

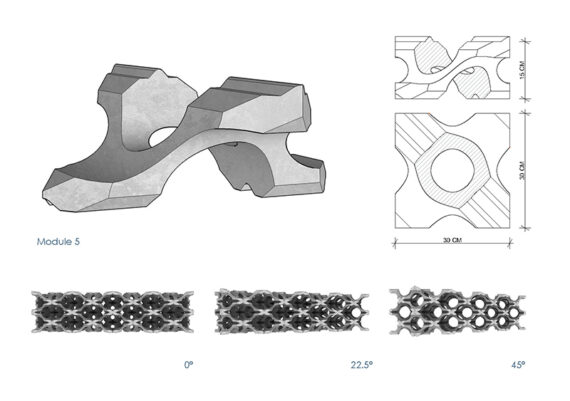

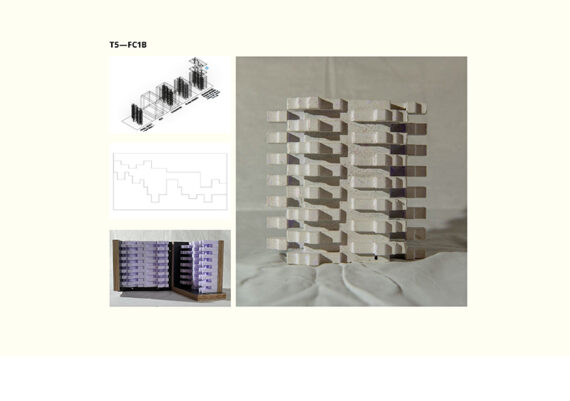

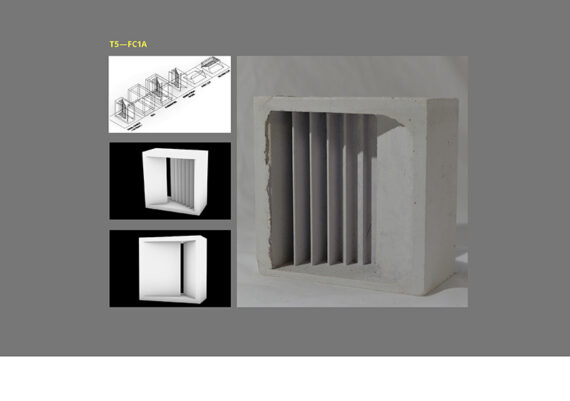

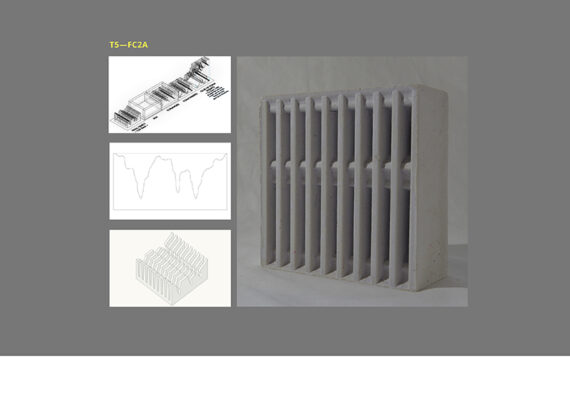

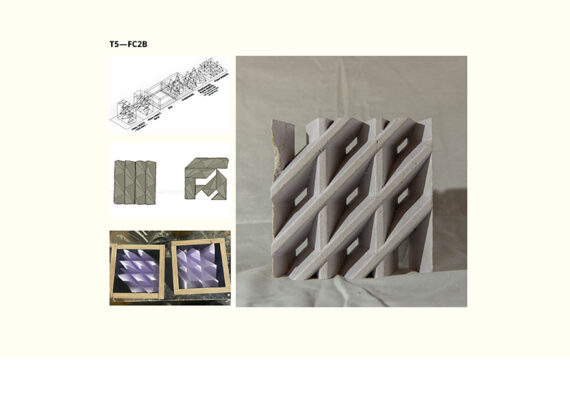

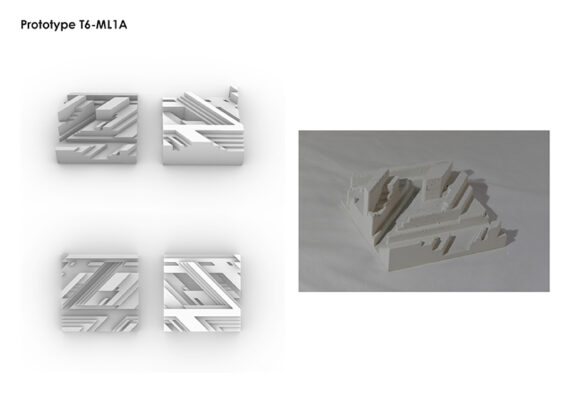

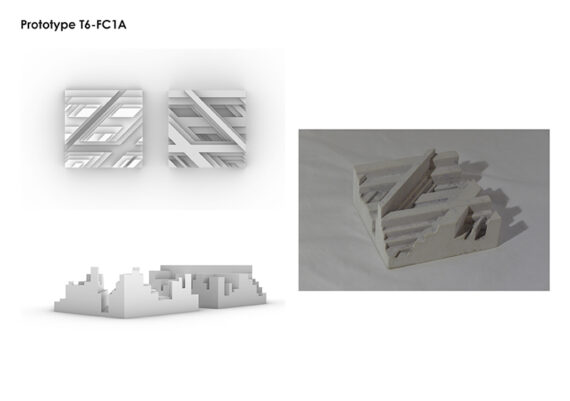

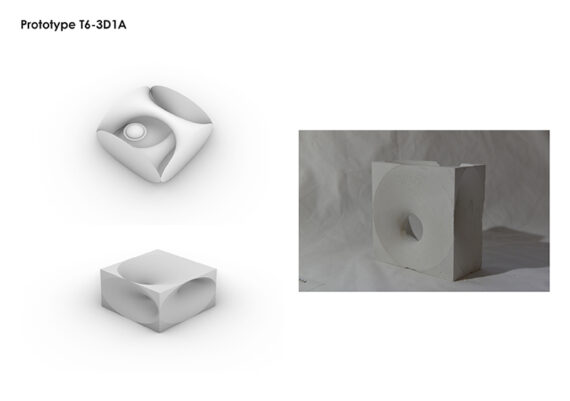

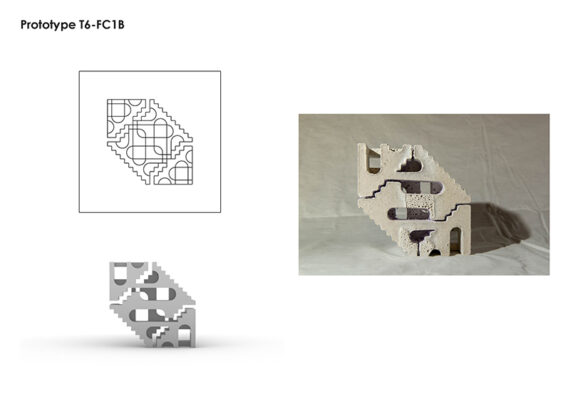

On the other end of the program, we assembled a small team to receive the design input from the participants, in a variety of software programs and file types, to be developed into manufacturing code for three different fabrication techniques. We offered 3D-printing in PLA, CnC FoamCutting and CnC Milling in foam to produce formwork or inserts for formwork. The participants were organized in five teams of three or four students to ensure that students from different countries had the opportunity to work together. Each team were given the opportunity to test all three fabrication techniques.

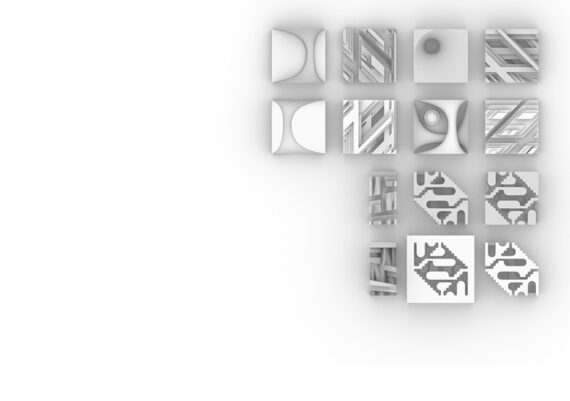

The assignment for the students was as open as possible with the only restrictions on maximum sizes and volume of concrete, all due to production limitations. We planned to produce seven objects per team over the five days. This setup made it possible for teams to try most fabrication techniques at least twice, thus presenting them with an opportunity to not only experience the limitations of fabricating the formwork and the concrete objects, but to also develop a second iteration taking in account the learnings from the first.

The main challenges for the participants were not the online digital setting of the master class, nor the limiting restrictions of the assignment; far more challenging were the limitations of the digital fabrication methods as well as the physical limitations of working with concrete in objects with such small dimensions.

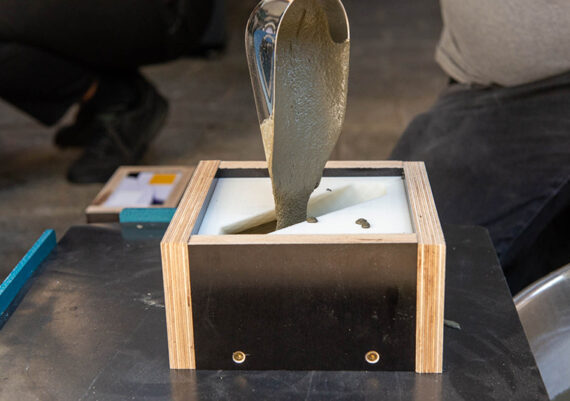

3D printing in PLA for example results in a very rigid formwork that is hard to demould when complicated or especially delicate shapes are intended. CnC foam cutting is a process in which a straight hotwire is directed though a piece of foam with a 4-axes freedom (two axes on one side, two on the other) that offers some very specific form possibilities and that at the same time presents the designers with very unusual restrictions. Similarly, CnC milling has its own restrictions; the main one being the depth of the cutting bits. Beside all these machine features another important restriction was the fabrication time per technique, we had to stay aware of our ambition to produce 35 objects in five days; from design to demoulding.

Lastly, the concrete itself offered major learning opportunities. Although we used a high-performance concrete without coarse aggregates, the formal limitations were exceeded more than once. Designing too slender or too complex geometries, combined with rigid formwork and short setting times led to many issues and breaks during the pouring – such as concrete not reaching all the formwork - as well as the demoulding process. Nevertheless, we were able to obtain an impressive ‘grid’ of prototypes - a true overview of the potential of concrete, of formwork techniques, and of this collaborative digital working environment.

The virtual master class proved to be an intense, energetic and exiting experience. Participants were asked to deliver design decisions and results at an unforgiving pace, while collaborating with colleagues they never had met before, with a variety of skills and interests. They did extremely well. In terms of complexity of objects, investigating the potential of the fabrication techniques, the proposals far surpassed our expectations. This presented the fabrication team with their own unexpected challenges. The intended iterations of tests and prototypes reached a maturity, complexity, and refinement we have never seen before in our hands-on master classes. A sign that this virtual program led to more focus and commitment to the design program than before.

Of course, we did miss the in-person contacts that have characterized the Concrete Design master classes thus far. The international exchange of ideas and experiences, the talks, the collaborative spirit and not least the actual physical process of working with the materials.

Fortunately, we did at last get the opportunity to meet up in Dublin during the last week of October. With COVID-19 restrictions more relaxed than in August, it was possible to come together for a weekend in which the objects and formworks produced from afar could be seen, touched, and examined in detail on textures, colour, and form. And we managed to talk directly and celebrate the winning of the competition at last!

CONCRETE DESIGN MASTER CLASS ON FORM-WORKS

Participants:

Leander Decloedt, Koen van Dijk, Luis Frisch, Vanja Jovancic, Andras Kispal, Jemina Lai, Florian Lapport, John Moran, Kate Newe, Wouter Persyn, Katy Rea, Leo Ritter, Mirthe Schots, Alex Tsalkizidis, Dries Voet & Ine Verhaege

Tutors:

Siebe Bakker & Gregor Zimmermann

Experts, critics and lecturers:

Alan Dempsey – Nex Architecture, Guy Mouton – Mouton, Anca Timofticiuc – Mensing Timofticiuc Architects, Diederik Veenendaal – Summum Engineering & Gregor Zimmermann – G.tecz Engineering

Fabrication team:

Siebe Bakker, Camille Gbaguidi & Kathryn Larsen

Photography:

Robin Bakker & Laura Stassen

The Concrete Design Master Class on FORM-WORKS has been made possible through the support of: FEBELCEM & InformationsZentrum Beton, Irish Cement & Tektoniek University / Betonhuis|Cement